ON EXPOSURE 1/3

EXPOSURE. EXPOSURE. EXPOSURE. I say its name three times while looking in the mirror, but it doesn’t disappear. So the next best thing I can do is write a long ass essay about it.

This is a letter of The (Im)posture — the newsletter from Julien Posture. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing

Chapter 1 : Being seen

I opened my eyes early this morning. Not ready to get up yet, I lingered in bed, grabbed my phone and opened Instagram. While my eyes were still half glued together by sleep, the screen barged into my pupils with its bright, cold light I hurried to turn down to an acceptable level. I swiped story after story, made a quick detour through the main feed to finally settle on the uncanny explore page, a sobering reflection of my algorithmic self. Shirtless men, baking goods and illustrations. The reels go by fast, mindless, I never really understand any of them, of why they are here and wonder if around me everyday in every home, everyone is performing little dances in front of their camera. I couldn’t describe what I’ve seen this morning on Instagram, it’s all gone, probably for the best. The parade of images, videos, sounds, brands, people, artists I witnessed, turned into electric signals in my retina, merely flashed through my occipital cortex to almost instantly trigger the production and release of dopamine in the reward pathways of my brain. In that moment, it struck me - probably because I new I had to write this essay later - that my mindless gazing at my screen was the fabric of what we call “exposure”. As a person, which means as a consumer, which means as a looker, the attention economy constantly exposes me to countless stimuli that some have paid for me to see. Needless to say, my 6 am puffy eyes, blinded by a screen, wired to my semi-asleep brain, didn’t feel like they were worth much. Yet, I was providing what later today I might be offered as income, to be seen.

The problem of exposure is like a one-way mirror. These windows we often see in detective movies appear to be a mirror on one side, but a see through window from the other side. They are actually half-silvered glass that reflect less light than a regular mirror in a particular lighting setting. The interrogation room is always well lit while the observer’s side is kept in darkness. If we were to light it up, the effect would fall and the glass would appear as a fuzzy window from both sides. Talking about exposure seems to always be limited to a mirror conversation about how we, individual artists, should say no to it. As if our only power was refusal. In doing so, exposure keeps evading a critical gaze, always occulting the conditions of its emergence, of its mechanisms, leaving us alone with the weight of the decision, to work or not for exposure. But like a true one-way mirror, this trick of the eye is only possible when the other side is kept in darkness. Once we cast some light on it, we might be able to move the conversation away from individual failure and bitter twitter accounts to identifying systemic failures at the heart of the problem. This essay is a 3 part attempt to start doing just that. In today’s part, I’d like to look at the conditions of emergence of visibility as a form of capital in the XXth century and the value of being seen in the media saturated world we live in. Part 2 will look into the economic conditions that maintain exposure and the problem of convertibility from exposure to money. Finally, Part 3 will take a stab at deconstructing some of the major logical flaws of exposure logic and question how we define value and success for the future of the creative industry. So buckle up, let’s talk about exposure.

A brief history of being seen

Before exposure, there was visibility. Visibility refers to the visual aspects that constitute our social relations. Sociologist Andrea Brighenti identified 3 types of visibility : Visibility as recognition, visibility as control, and visibility as spectacle. The latter one is where exposure stems from. Visibility as spectacle is tied to media technologies (Cinema, TV, internet, etc.) through which we project illusory images - of fame, beauty, success- that shape our real lives and how we relate to each other. Of course, the desire to be seen has existed long before new media. From the antiquity on, being seen and recognized was important, especially regarding political power. Until the invention of printing techniques and other multiplication media, there were two main ways of being seen publicly, either by commissioning an artist to create a portrait, or by organizing a public event in which the person would be exhibited. Here you can already see how both these options would rely on a hefty amount of economic and social privilege. Having one’s portrait painted/sculpted/carved and displayed was extraordinarily expensive (meanwhile last Christmas I ordered an oil portrait of my dog from a local artist, and yes, it’s gorgeous). Similarly, organizing a public event required pre-existing social status to draw in the masses, something that only queens, kings, and politicians could achieve1.

It’s hard to imagine today, in our face-saturated media environment, the feeling it must have been to live in a world in which most people we saw were seeing us as well, shop owners, neighbours, family. A world of mutual recognition. And then the feeling it must have been to know one person’s face from a portrait or an event while being part of a faceless new formation, an audience.

Flash-forward a few centuries, we got used to being an audience but this was only the beginning. The invention of the printing press introduced the idea of mechanical reproduction of words and then of images thanks to lithography. Photography came along and provided even more detailed, faithful depictions of what we now call “celebrities”. Came cinema, and later television, with their share of exceptional individuals whose main job was to be looked at. While it’s true TV put the bar really low in terms of who got to be seen and recognized, there were still a fairly high degree of gate-keeping regulating access to these platforms. The internet blew up those gates. Now, to have a cellphone means to have a potential visibility and social media and their retweets and shares have unlocked the viral spread of such visibility to millions*.* For anyone with a Tik-Tok account, the boundaries between being visible and being an audience are more porous than ever.

The spectacle of visibility is not limited to a few media or to a brief event, it is 24/7. Building on Guy Debord’s classic La société du Spectacle, philosophers Gilles Lipovetsky and Jean Serroy suggested we now live in a society of hyperspectacle, which

“designates the society of the ‘all-screened’, where the increasing number of chains, channels and platforms is accompanied by a profusion of images (information, films, series, advertisements, varieties, videos ...), that can be seen on different screens in any size, any place and any time. The global, multifaceted and multimedia screen is triumphing, imposes the age of spectacular abundance” p.274

So here is our cultural basis for the emergence of visibility, and ultimately, exposure. The constitution of an asymmetrical audience-celebrity relationship, a media regime of potential infinite, viral, growth and an easier-than-ever access to the means of visibility. In this context, the leap from being seen to getting paid is a short one. But what is the nature of that leap ? How do we go from being seen as a cultural practice to exposure as a form of currency ?

The value of being seen

Philosopher Walter Benjamin, in his famous essay The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility examined how photography and other means of infinitely reproducing images changed our relation to artworks, and ultimately, their nature. For him, the reproduction of an artwork will always lack the “here and now” of the original, the experience of being in the presence of an artwork at a given place, in a given time. This special something that is supposedly lost in a reproduction is what Benjamin called its “aura”. More recently, Sociologist Nathalie Heinich challenged that notion, suggesting that it was actually the diffusion of reproductions of an artwork that participate to growing its aura. If you hadn’t spent your life seeing reproductions of La Joconde, in magazines, books, reels, etc. framing it as the most famous and important piece of art, you probably wouldn’t care that much about it being smeared in cream. For Heinich, it’s the very multiplication (i.e. increased visibility) that gives its unique value to an artwork.

These two perspectives on value and reproduction are more than philosophical debates about art. They parallel the very ways we give economic value to different types of art today and how different types of artists make a living. Original artworks circulating in the fine art industry cost more than prints, even when the prints are not reproductions of an original, but artworks in their own right. Here their uniqueness is value. On the other hand, in the illustration industry, the more an image is distributed and multiplied, the more its value increases. We index the cost of a licence on the amount of eyes that will look at an image. Here, reproduction is value.

Back to visibility, Heinich tells us that one of its key feature is an asymmetry in numbers between who is seen and who sees. This difference creates a real form of resource disparity between the two categories of persons and can therefore be understood as a form of capital. Capital is a term most commonly used to refer to the economic entity of accumulated labor, appropriated by someone, the capitalist, and used to generate profit which he can then invest in ways of accumulating more capital and so on and so forth, in an infinite cycle of extractive growth. But the notion of capital has been expanded, most notably by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu :

“[…]capital can present itself in three fundamental guises: as economic capital, which is immediately and directly convertible into money and may be institutionalized in the form of property rights; as cultural capital, which is convertible, in certain conditions, into economic capital and may be institutionalized in the form of educational qualifications; and as social capital, made up of social obligations (“connections”), which is convertible, in certain conditions, into economic capital and may be institutionalized in the form of a title of nobility.”

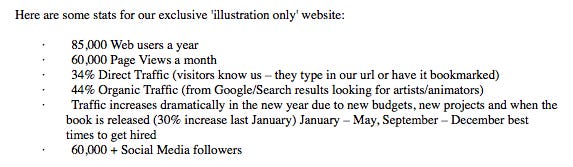

For an example closer to the creative industry, a studio space or a home you’ve purchased would be economic capital, a BFA, or growing up in an artsy family would constitute cultural capital and social capital would look like nepotism, getting hired through knowing someone in the biz, etc. Heinich considers visibility as a fourth form of capital in itself as it acts as all the above and is “measurable, accumulable, transmissible, generating interest, and convertible” (p.46). For example, as many of you, I’ve been contacted many times by a promotional organization proposing to showcase my work on their website for a fee of 82$/month. Part of their speech was to show me how much exposure they could offer through various metrics :

By focusing on quantifiable metrics of followers and visits, this organization was doing the transformation labour of turning visibility capital into economic capital. And in a way, it is true that visibility takes work. Think of how much Instagram requires from creators to work for it in order to be seen. Engaging, commenting, following, clicking, scrolling, etc. are practices IG requires us to partake in, in exchange of showing up more regularly in our followers’s feeds. This is the nature of the attention economy, what Dr. Crystal, working with influencers, has called “visibility labour” :

“Visibility labour is the work individuals do when they self-posture and curate their self-presentations so as to be noticeable and positively prominent among prospective employers (Neff et al., 2005), clients (Duffy, 2016), the press (Wissinger, 2015) or followers and fans (Abidin, 2015, 2016; Duffy, 2016; Wissinger, 2015), among other audiences.”

But unlike what the organization selling online portfolio would like us to believe, visibility only equates economic value under certain circumstances, numbers are only one side of the story. So far, all the authors we’ve talked about were dealing with celebrity as in, people who get recognized by their face. When your very own face is the object of the visibility, you don’t need to worry about it circulating without you or your name. When it comes to artworks though, we need a more nuanced understanding of how visibility can be converted into money as well as the distinction between quantity and quality of visibility.

Visibility exposed

The study of visibility has been one of personality. From Antiquity portraits to today’s selfies, being recognized starts with a face. Considering this background, it might be tempting to apply the same principle to the visibility of artworks. After all, in our society, artworks are considered parts of an artist, a direct expression of their inner self. Seeing an artwork is a bit like seeing an artist. At least that’s how romanticism and copyright law have framed it. But in practice, things are messier and in the media world we live in, artworks can circulate easily without any trace of their authors. No one can pretend to be Charlize Theron to be cast in a commercial for perfume in her place, but everyday we see cases of companies ripping off artist’s work without their consent2.

Unlike faces, for the visibility of an artwork to be understood as a form of capital, and therefore to have an economic value, certain conditions need to be met. The concept of crediting for example stems from such need. A few months ago, someone from an advertising agency reached out to purchase one of my prints to hang it in the background of an ad for a big grocery store chain in Québec. I asked for a licence fee but they wanted to pay only for the print itself, arguing that this was just a background image and that the ad would be see on TV for a while (= lots of yummy exposure). I had to explain that this set of conditions wasn’t producing a valuable visibility for me, in the absence of a proper credit, I wouldn’t be able to convert the supposed visibility into economic capital (future contracts) or even social capital (connections, people remembering my name) because no one could link the work to me.

Another example of such failure of producing value out of exposure would be exposure to irrelevant eyes. Imagine a scenario in which the Association for Pet Obesity Prevention would ask an illustrator to work for exposure in their community. In this case, exposure would mean to be seen by a bunch a veterinarians concerned with pet obesity. Not exactly the most likely demographic to hire an illustrator in the future. I already hear some say “you never know !” but hope labour is a theme of the second chapter of this series on exposure, so bear with me.

Absence of credit, irrelevant audience, and many more factors can render visibility worthless to an artist. Organizations that propose exposure focus on sheer numbers, quantity, because they know that a qualitative assessment of the exposure they offer would show it to be useless economically.

Let’s recap. We’ve seen that the XXth century technological moment created a rapid development of mass representations alongside a deeper and deeper asymmetry with a few people getting seen by a lot of people they don’t know. This difference in visual resources created visibility as a form of capital many creators in the attention economy are trying to turn into a living. This being said, artists face particular challenges in terms of converting visibility into money and the exposure they often get offered should be considered in terms of quality instead of quantity. So far I sided with academics and used visibility and exposure as interchangeable terms but for the rest of the discussion we need to be more nuanced, so here are 2, slightly heavy definitions of each:

Visibility is the capacity of being seen, directly or through images, that in a particular economic and cultural context (e.g. our capitalist media environment), may constitute a form of capital that can, in certain conditions, be converted into other forms of capital, notably economic.

Exposure is the capacity of being seen, directly of through images, that always presents itself as a form of capital with great value (often through the use of quantifying metrics) but lacks key (qualitative) elements in order for its value to be convertible into other forms of capital.

So while visibility carries the potential to be turned into value, but doesn’t not necessarily needs to be, exposure is always a value proposition, even when it actually can not, realistically, be turned into value. I hope this foray into celebrity, visibility and exposure from a sociocultural perspective has shed some light on the rich set of factors that got us to the point of being constantly proposed exposure as salary. Exposure is a complex phenomenon and I don’t think it’s enough to simply discard it or refuse it. We need to dissect it in order to dismantle it properly. This series is just a tiny stab at this project and I hope you’ll find it helpful to think through this endemic issue of our profession.

Let’s light up that false mirror.

If you enjoy receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please consider going to the paid version. The paid version is exactly the same as the free one. This is because I believe paying for someone’s creative work shouldn’t be about paywalling readers but about “payspringboarding” writers. If you agree and can afford it, you can switch to the paying version here.

You can also follow me on Twitter or Instagram. This letter is the start of a conversation, don’t hesitate to share it to someone who might like it, or to like or comment below.

An exception to that rule would be public executions, but I’m limiting the present discussion to desirable visibility.

The exception to this might be a classic “artist in the studio” video that brands seem to increasingly love. Videos accompanying an illustration project in which we see the artist at work, their commute, their week-end trip for inspiration, and sometimes a carefully scripted plug for the brand they worked with are more and more common in our industry. One of my favourite artist, Geoff McFetridge, in the last year only has been shot by DropBox, Vans, and Norse Project, to the extent it is now easier to find the videos about the projects than the projects themselves. But this is not about exposing the face of the artist, it’s about romanticizing curated parts of an, ideally stylish, artist’s lifestyle in order to contribute to a brand’s value.