Note that this essay is best experienced in your browser, on a big screen. The email version has been truncated and the mobile version won’t display the right scale of the images.

Good morning dear On Lookers!

If you’re reading this from North America, chances are you’ve heard that today is your chance to see a total eclipse. To celebrate this rare cosmic event (maybe twice in a lifetime depending on how far you’re willing to go for an eclipse), here is a visual essay connecting images in a constellation that I hope will feed your umbraphilia.

Eclipses happen all the time, especially on other planets. But as anthropologist Anthony Aveni has pointed, Earth’s eclipses are a special treat:

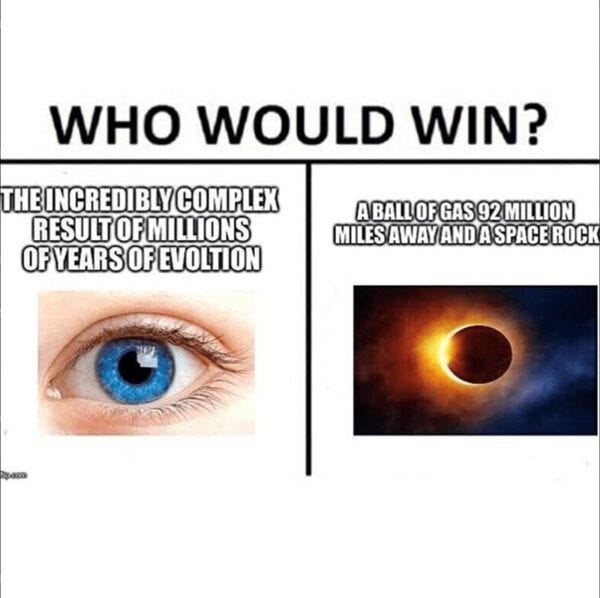

With sixty-three moons to gaze at, hypothetical eclipse chasers situated at the top of Jupiter’s perpetual cloud deck could experience lots of eclipses, but not one of the moons perfectly frames the sun, which, at Jupiter’s distance, is only one-fifth as wide (and one-twenty-fifth as bright) as seen from earth.

We may be taking it for granted, but the perfectly neat image we have of an eclipse is the result of a goldylock effect between our eye, the moon and the sun.

Under other circumstances, we might not have been so lucky, ask Mars.

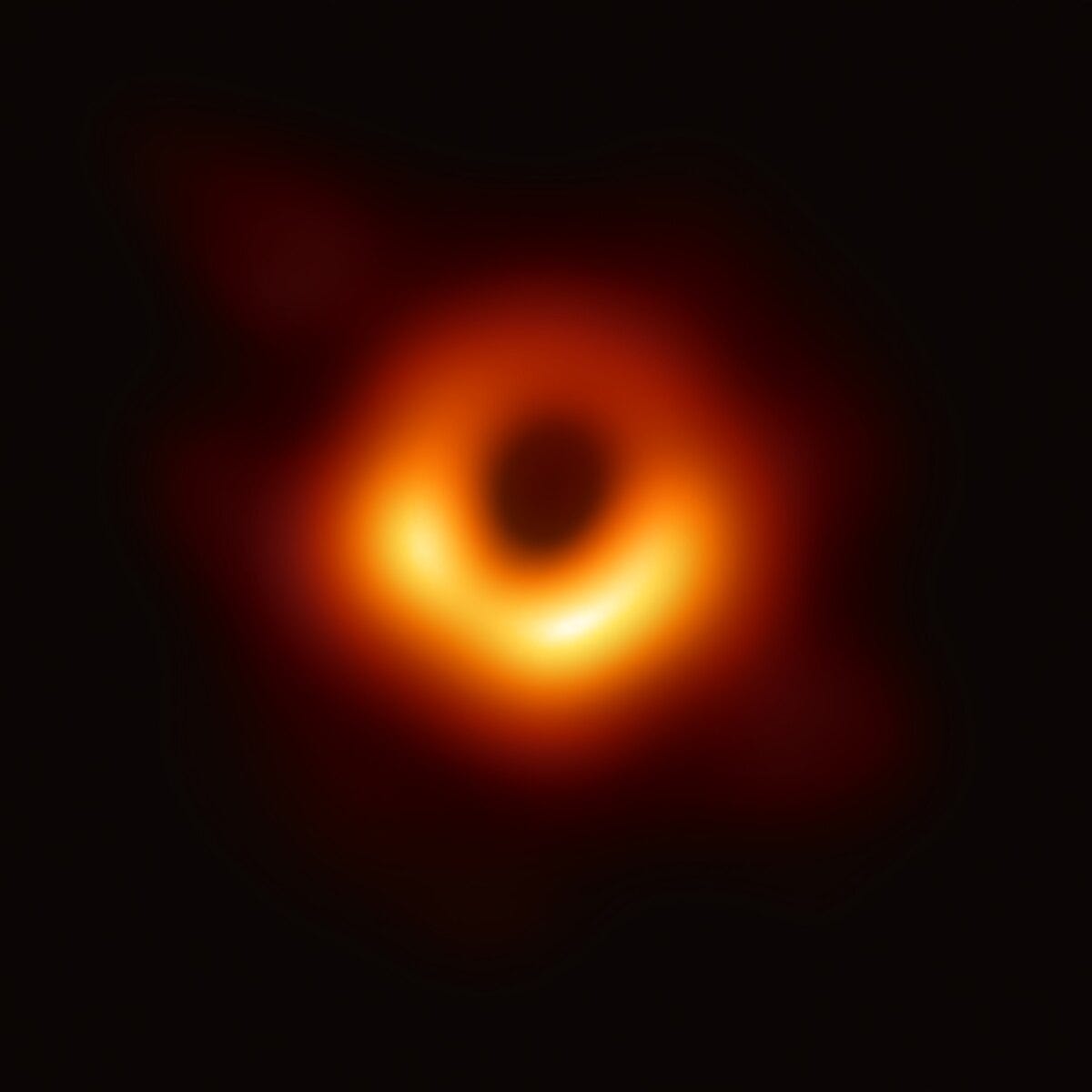

What I love about cosmic events, is their defiance of visual reduction.

They just won’t yield to the camera.

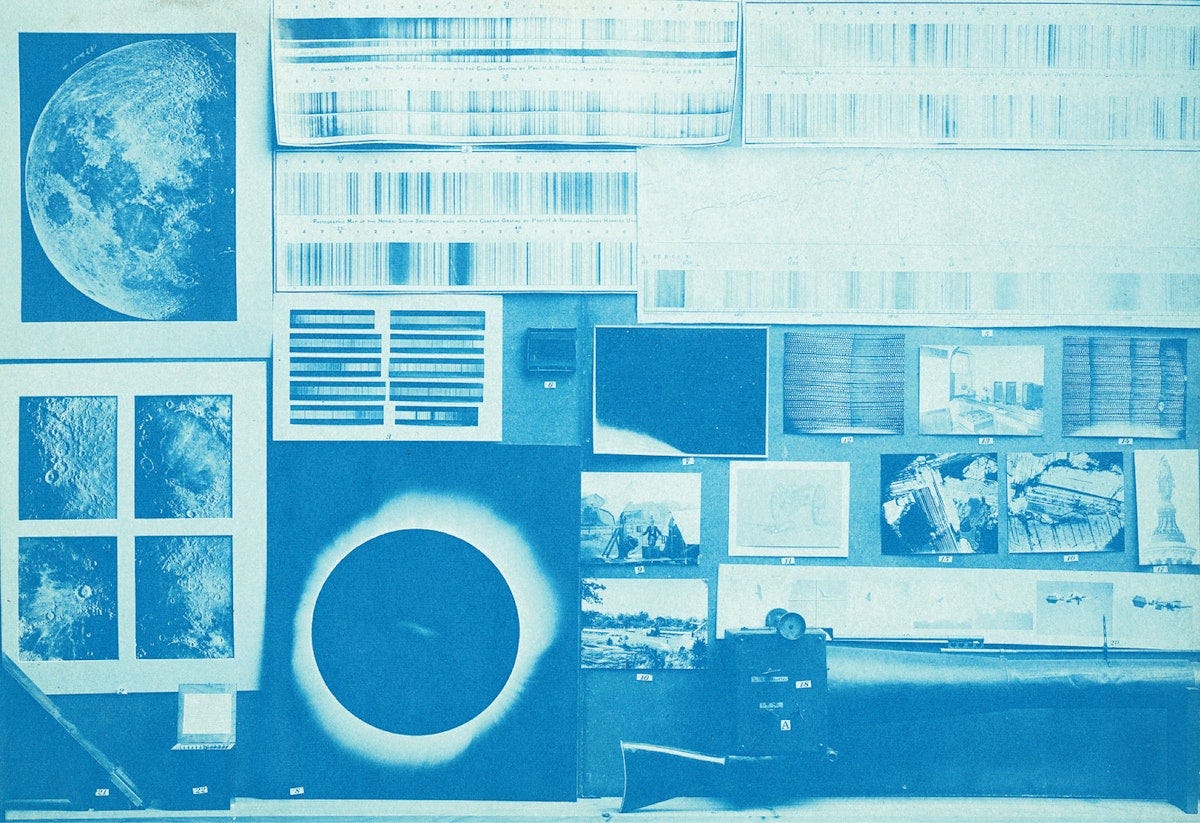

8 radio observatories to capture a black hole in 2022.

22 negatives to capture an eclipse in 2001 — 100 exposures in 2017.

1 drawing in 1878.

The challenge to our image capture technologies is also a challenge to our sense of the real.

Eclipses affect the colours around us, reminding us that our perception of the world is a partial transcription of electromagnetic waves by our brain. During an eclipse, our eyes become more sensitive to the blue end of the spectrum, and things around us appear draped in shimmering green and violet hues.

For a second I think of Dune’s Giedi Prime and its black sun which was beautifully rendered by Denis Villeneuve as a monochromatic world.

Perception involves blind trust to one’s senses.

A while ago I was having an argument with a friend after mentioning that magenta didn’t exist (by which I meant, physically exist) because there’s no electromagnetic frequency associated with it and is only made up by our brain. This resulted in hours of meandering explanations and clarifications, about the words we use and the world we see, yet he never accepted that magenta doesn’t exist.

(sorry Antoine, magenta doesn’t exist, get over it)

Eclipses are something to look at, yet they are always also something dangerous to look at.

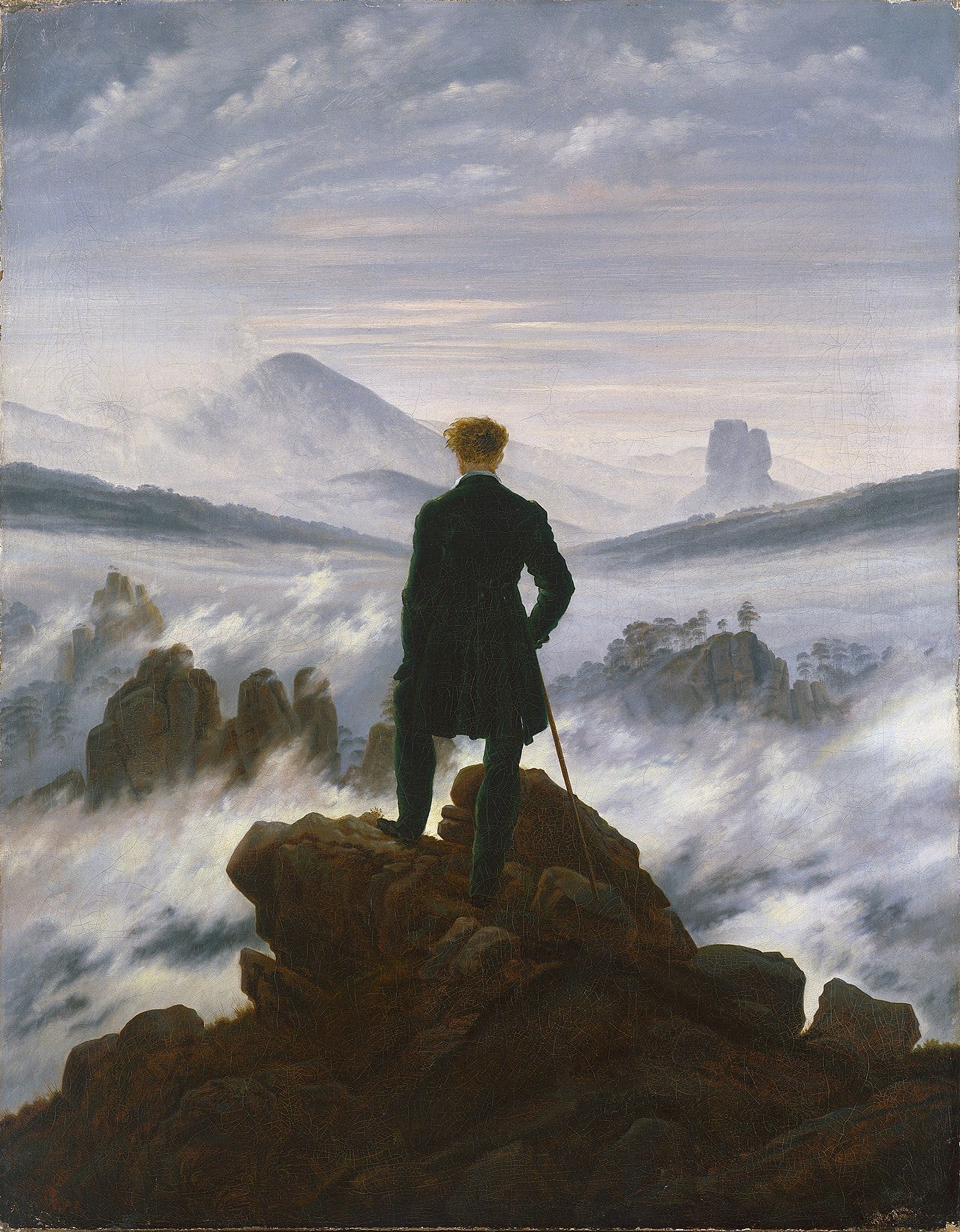

The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully is Astonishment, and astonishment is that state of the soul in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror … No passion so effectually robs the mind of all its powers of acting and reasoning as fear. For fear, being an apprehension of pain or death, operates in a manner that resembles actual pain. Whatever therefore is terrible, with regard to sight, is sublime too … Indeed terror is in all cases whatsoever, either more openly or latently, the ruling principle of the sublime.

That’s Edmund Burke, in “A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful” (1757).

It’s a cruel, yet necessary, joke that the most beautiful things in and out of this world are impossible to look at.

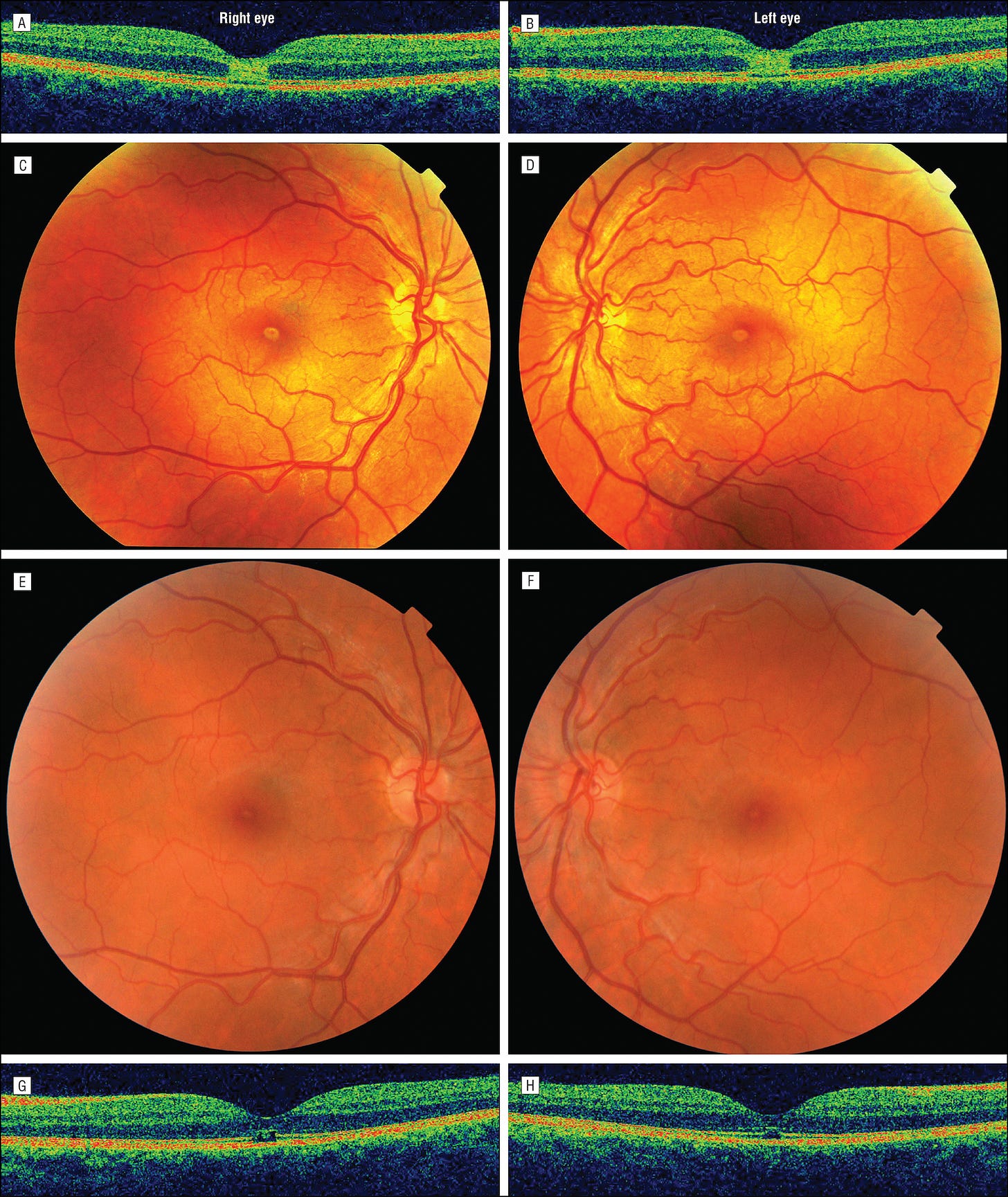

Looking at an eclipse without protection will cause a solar retinopathy.

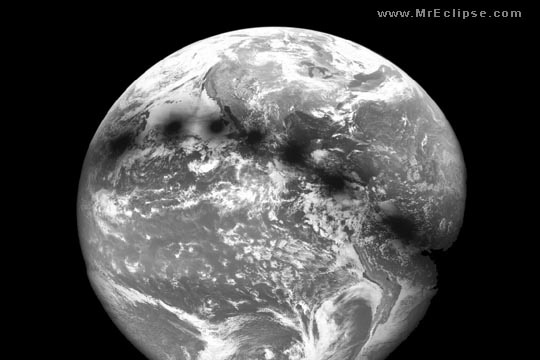

Solar retinopathy looks like an eclipse on the retina.

Shadow on the planet, shadow on the eye.

So don’t look up (without protection). The eclipse is the original cautionary tale about the danger of looking.

“SHUT YOUR EYES MARION!”

“SHUT YOUR EYES MARION!”

“SHUT YOUR…”

Anyway.

The experience of the sublime described by Burke is, in a very 18th century fashion, tied to individual experience.

But as the experience of the sublime dissolve the self, let it be an opportunity to connect with others.

Helen Macdonald says it best.

The millions of tourists who flocked to the total eclipse of 2017 didn’t see something time had fashioned from American rock and earth, nor something wrought of American ingenuity, but a passing shadow cast across the nation from celestial bodies above. Even so, it’s fitting that this total eclipse was dubbed The Great American Eclipse, for the event chimed with the country’s contemporary struggles between matters of reason and unreason, individuality and crowd consciousness, belonging and difference. Of all crowds the most troubling are those whose cohesion is built from fear of and outrage against otherness and difference; they’re entities defining themselves by virtue only of what they are against. The simple fact about an eclipse crowd is that it cannot work in this way, for confronting something like the absolute, all our differences are moot. When you stand and watch the death of the sun and see it reborn there can be no them, only us.

So grab a pal,

grab a lover,

go to the park,

and look up,

together.

This is my first photo essay! Let me know in the comments what you think of this format and if you’d like to see more, I’m curious to know if it feels as relevant to read as it felt fun to write.

such a fun photo-essay about the eclipse!

Yes, 'twas a fun read. More photo essays, please!